The Body of Christ: The Ultimate Foundation and Full Realization of the Unity of Truth and Love

José Granados

This is an extended version of a paper presented at the Veritas Amoris Conference: “The Truth of Love: A Paradigm Shift for Moral Theology” on June 26, 2021 at the Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio, USA.

“I am the truth” (Jn 14:6). “In this is love, that he laid down his life for us” (1Jn 3:16). These two sentences by St. John the Evangelist summarize the mystery of Christ as being the union of truth and love. First, Jesus of Nazareth, the very one the disciples heard preaching with authority, is the truth in person. Secondly, John describes Jesus’ self-giving unto death, not only as an excellent act of benevolence, but as the very definition of love.

This approach to Jesus is crucial in facing the crisis of our time, which can be described as a divorce between love and truth. On the one hand, truth today means the truth of raw facts or scientific data, which have little to do with the meaning we search for our lives. For today’s truth is alien to the realm of love and, thus, to the good that gives direction to our steps. On the other hand, love, separated from truth, is confined to private affection, with no possibility of sustaining itself over time or of influencing public life. For if contemporary society recognizes any truth beyond scientific truth, it is only the following: to tolerate that each one can have his own truth, which means that nothing is true beyond the feelings of the individual (cf. K.H. Menke, La verdad nos hace libres o la libertad nos hace verdaderos? Una controversia, Madrid, Didáskalos, 2020).

The fracture between love and truth is a fracture that goes through the person himself, for this fracture separates our interiority from our exteriority; our intimacy from our communion with others. If the Church were to accept such a fracture, she too would be cracked, for she would separate her confession of faith from her experience of life; her doctrine from her pastoral ministry; her liturgy from her mystical union with the Lord. The Veritas Amoris Project focuses on proposing a unitary vision between truth and love, finding in this unity the key to understanding who man is and what gives fullness to his life.

This second thesis of the Veritas Amoris Project seeks to explore how Christ brings with him the fulfilled unity of truth and love. If we believe that “only in the mystery of the incarnate Word does the mystery of man take on light” (Gaudium et Spes 22), this applies as well to the truth of love as a key to understanding human life. What the truth of love is all about, takes on light only if we look at Christ. And, at the same time, the mystery of Christ can best be perceived if we start from the truth of love as the key to understanding man, the world and God.

To explore this topic, I will first link Christ to the unity of truth and love (1). I will look then for the appropriate vantage point to perceive this unity in his person and work (2). Finally, I will focus on the Gospel of John to show the different ways in which Christ and the truth of love go together, since John has placed special emphasis on this connection (3).

1. Access to Jesus Christ: Starting from the Unity of Truth and Love

Let us begin by recalling that the work of Christ is a work of unity. He is one with the Father (Jn 10:30) so that, through him, God might “reconcile the world to himself” (2 Cor 5:19), thus bringing together “the scattered children of God” (Jn 11:52). He, as “Alpha and Omega” (Rev 1:8), also links the beginning and the end of history. This is why Jesus can look back to the origin of creation and reaffirm the unity between man and woman, symbol of God’s unity with his people throughout history: “What God has joined together, let no man put asunder” (Mt 19:6). Does this not mean that he also brings unity to truth and love, that is, that he brings together the world we share with others, on the one hand, and the intimacy of our affective world, on the other?

And how can we explain this unity between truth and love? Today everyone accepts that Jesus is love, while it is more difficult to accept him as the truth. “I am the truth” (Jn 14:6) is a stumbling block, unless it is interpreted as tolerance for the opinions and feelings of each individual. The key to understanding Jesus would be the love that “bears all things” (1 Cor 13:7), but not the love that “rejoices in the truth” (1 Cor 13:6). The overall vision of this tolerant love would allow, according to some scholars, to relativize certain expressions of Jesus that sound too harsh. The German exegete Ulrich Luz, for example, accepts that the absolute prohibition of divorce comes from Jesus himself, but adds that this is an incoherence that does not fit well with Christ’s general message about the primacy of merciful love (Das Evangelium nach Matthäus, Düsseldorf, Benziger, 2002, ad locum).

To heal this division, it is possible to take two complementary paths. We can start from Jesus as the one that we have experienced as our friend who loves us. We will then show that in him there is a common truth for all of humanity. Alternatively, we can start from the common truth he discloses openly to the world. We will then show that this truth contains within itself the love that touches and transforms us internally.

I want to choose this second path, even though it may seem at first to be more difficult, and without forgetting that the two complement each other. The reason for choosing this path is that, in our time, it is easy for the first not to reach its goal, that is, for love to Christ (reduced to an interior emotion) to turn in circles around itself, without confessing Christ as the common truth, but only as my truth. This is so because of contemporary emotivism, which values things according to the feeling they produce and thus prevents us from escaping the centrifugal force of the emotions.

This second path, moreover, is the one followed by John’s Gospel, which, as I said before, insists on highlighting the unity of truth and love in Jesus. The Fourth Gospel has been characterized as the one that starts from above, from the divine Logos, to bring us to Jesus, while the Synoptic Gospels are characterized as a path from below, from the preaching of the Jesus of history, which seems to be closer to daily experience. However, a better way to describe the dynamism of John’s Gospel consists of seeing it as an account that begins with truth to arrive at love. In other words, John begins with the word or light that awakens us from sleep and introduces us into a common world (Jn 1-12) so that, through our personal encounter with Christ, he comes to dwell within us as love (Jn 13-17). Something similar we see in the First Letter of John, where we move from “God is light” (1 Jn 1:5) to “God is love” (1 Jn 4:8). In this John goes hand in hand with the Synoptics, for the first word of Jesus is: “Repent!” (Mk 1:15), that is, “Awake, by welcoming God’s truth into your life.”

In what does the truth that is Jesus himself consist? The sentence “I am the truth” (Jn 14:6) refers to a revelation. Truth, then, could be understood as Jesus’ invisible divinity which manifests itself through the veil of the flesh. This exegesis has been proposed by Rudolf Bultmann, for whom the affirmation that Jesus is the truth means that he is the immutable divine Logos, which calls us to take the side of eternity against the appearances of the inauthentic world. However, in his two volumes on Truth in St. John (La vérité dans Saint Jean, Rome, Biblical Institute Press, 1977) Ignace de la Potterie has rejected this interpretation, noting that St. John does not directly identify truth with God. What is, then, this truth that Jesus brings with him?

2. A Eucharistic Starting Point

Let us follow this clue: when St. John speaks of Jesus as truth, he generally does so in a liturgical context. Thus, after saying that the Word has become flesh, in the context of the theology of the temple (“he dwelt among us” and revealed his glory), John says that Jesus is “full of grace and truth” (Jn 1:14). And in his dialogue with the Samaritan woman, Jesus, referring to the true temple, speaks of worshipping “in spirit and truth” (Jn 4:23). Later on, during the so-called priestly prayer he asks the Father to “sanctify” the disciples “in truth” (Jn 17:17). The sentence “the truth will make you free” (Jn 8:32) is placed in the context of the Feast of Tabernacles, which commemorates Israel’s departure from Egypt. Moreover, Jesus says “I am the truth” while explaining how he will lead us to the many dwelling places that he prepares for his disciples in the new temple, which is his body (cf. Jn 14:2; Jn 2:21).

This liturgical context leads us to the Eucharist, Jesus’ central rite, as the proper place for understanding what he means by identifying himself with the truth.

a) The Truth, from the Vantage Point of the Eucharist

Let us recall that Jesus says “I am the truth” (Jn 14:6) during the Last Supper. And there are also allusions to truth in the discourse on the bread of life. For there he speaks of the true bread (Jn 6:32: alethinós, as opposed to an Old Testament figure that is not the complete truth), and of the true food and drink (Jn 6:55: alethés, that is, the real one, in spite of the appearances). At the Last Supper, when using the image of the vine and the branches, with clear Eucharistic overtones, Jesus identifies himself with the true vine (Jn 15:1: alethinós).

To see how the Eucharist emerges as the place where the truth of Jesus manifests itself, let us recall that all of Jesus’ signs culminate in the Eucharist, for all his signs are fulfilled in his death and resurrection, which the Eucharist anticipates. Moreover, the Eucharist, being the bread of eternal life, brings with it the light of Easter, from which we can grasp the meaning of Jesus’ whole journey in time.

There exists, then, a relationship between truth and the body. This is confirmed by Ignace de la Potterie’s central thesis, who demonstrates that John proclaims Jesus be the truth because Jesus is the Logos incarnate. This means that truth is not what is eternal and immutable in contrast to the opinion of the deceptive senses and the movable affections. The truth is the Logos who has taken flesh and has manifested himself to our flesh, including our senses and our affections. Given this conclusion, we need to ask ourselves: what is the relationship between the body and the truth, so that the Eucharist can be the fullness of such a relationship?

b) Truth and Body

That truth manifests itself in a body is alien to the Cartesian vision predominant in modernity. Matter can be a place of truth, at most, inasmuch as its movements can be described with formulas. However, this is a very partial truth, which tells us nothing about the path of our life.

The situation changes if we accept that the body belongs to our personal identity. In this case, our identity, being bodily, needs to be understood as constituted in relation to the world and to others, to whom the body connects us. Classical philosophy has seen truth as a correspondence or adequation between the one who knows and the reality that is known. Well then, the body is the first correspondence between the person and his world and, therefore, the body is the space where the experience of truth can happen.

A conception of truth based on the difference between waking and dreaming is helpful here. The body, being at once interior to the subject and exterior to him, provides the criterion for distinguishing reality from dreams. For the “truth” captured in the dream is that of a correspondence between the mind and itself. Only the body allows us to enter a space that opens beyond ourselves, that is, a space from which we can know the world and manifest ourselves in it. Only from the vantage point of the body, then, can we speak of truth as correspondence between our vision and the real world (cf. G. Marcel, L’être incarné. Repère central de la réflexion métaphysique, in Du refus à l’invocation, Paris, Gallimard, 1940, 19-54; H. Jonas, The Phenomenon of Life. Toward a Philosophical Biology, Evanston, IL, 2001, 176).

Let us add that, among living bodies, only the human body opens the space of truth, because only man transcends his own point of view and is able to adopt the perspective of another. This is what happens with the interpersonal encounter, where the presence of the other person, irreducible to ourselves, awakes us from the isolated self-projections which are typical of dreams. The body appears then as a space of correspondence or adequation to the other person, a space that allows a shared vision of the world. In this way there is an enhancement of the experience of truth, since we no longer know alone, but together with the loved one. Hence the French philosopher Alain Badiou can say that love is a matter of truth, because it consists of having a common vision over a common world (Éloge de l’amour, Paris, Flammarion, 2009).

Indeed, from this encounter between persons, there emerges a shared vision, which is the vision proper to love. The body, therefore, expands the experience of truth, so that it becomes the experience of a common understanding of the world, where each person enriches the other. Adam experienced this new width of truth when, after naming the animals and repeating to each of them: “Not this one!”, he finally met Eve and said: “This is bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh” (Gen 2:24). At this moment he reached the correspondence with the other person that allows a complete vision of oneself and of one’s place in the world.

Moreover, if the body makes possible the correspondence of one person and another person, the body also opens the interpersonal relationship beyond itself, thus preventing the couple from dreaming together a shared dream. In fact, the body is a space of truth because it situates the relationship of two persons in the light of a common Origin that surpasses both and that opens their vision beyond themselves. Thus Adam and Eve, in accepting each other, accepted an original giver, the Creator, the one who had inscribed in their bodies the meanings that enabled them to be one in order to give birth to a new life (cf. Gen 4:1: “Adam knew Eve his wife”). The body turns out to be a space of truth because it differentiates visions that close in on themselves, from visions that recognize an origin and that, thanks to the light of this origin, extend their gaze over the world beyond themselves. The experience of truth proper to the body allows Adam to affirm, in the encounter with Eve: “Behold a body that manifests the person as someone that has been entrusted to me and that calls me to give myself to her. Behold a place where my vision opens up through the vision of the other person and towards the vision of the Creator who has united us.”

This understanding of the body, present in the Old Testament, clears the way for arriving at the truth of Jesus, which manifests itself precisely in the body. In Christ, in fact, the experience of truth that we find in every body reaches its fullness. In what follows I will show how the space of the fullness of truth is the risen body of Jesus, given up for us in the Eucharistic offering. In fact, the theological tradition has often added the word “true” precisely to the body: the body that Jesus assumed, the body that suffered and rose and ascended to heaven, the Eucharistic body. Thus the Church sings before the sacrament: “Ave verum corpus natum […] vere passum, immolatum.” This is a true body (corpus verum), not only because it is a genuine body, but because this is a body that manifests the fulfillment of the truth of God, of man and of the world.

To describe the truth disclosed for us in the body of Jesus, I will go through some texts of St. John’s Gospel, focusing on the association between truth and the body. This union between truth and body will help me show, in turn, that the truth I am talking about is the truth of love, and more specifically, the truth of corporeal love.

3. The Manifestation of the Truth in Jesus’ Flesh

John writes his Gospel from the fullness of the encounter with the Risen One, summed up in Thomas’ confession of faith in the face of Christ’s pierced side: “My Lord and my God” (Jn 20:28). To say, “Reach out your hand and put it in my side” (Jn 20:27) is a way of clarifying the meaning of the Eucharistic words “take and eat,” In the light of Easter, I will explore, as I said, how the truth of Jesus is revealed in his flesh and, in this way, how it appears as the truth of love. I have chosen four texts of John’s Gospel.

a) “Full of Grace and Truth” (Jn 1:14)

“And the Word became flesh … full of grace and truth” (Jn 1:14). The one, then, who is full of this grace of truth is not simply the Logos, but the Logos made flesh. This is what we also read at the beginning of the First Letter of St. John: “What we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life— this life was revealed” (1 Jn 1:1-2). The truth, which consists of the visibility of life (that is, the visibility of a living person), shines in the encounter with the body of Jesus, where the Word can be seen and touched.

“We have seen his glory.” John identifies the flesh of the Word with the tent where the Word dwells, that is, with the temple, as Jesus himself will later say to the Pharisees (cf. Jn 2:21). In fact, the space of the temple is such that once we are placed in it, we can experience the presence of the Creator and Father. The flesh of Jesus is identified with the temple because Christ is the Logos who, being from the beginning in the bosom of the Father, has manifested the Father to us (cf. Jn 1:1; Jn 1:18).

Therefore, the body is the place of a word that acknowledges the Father’s gift, that is, the place of a filial word. Notice that the prologue of John’s Gospel, which begins with the Word, ends with the Only-begotten Son (Jn 1:14; Jn 1:18). In between we find the birth of the Word in the flesh, which explains the passage from Word to Son: if it was possible for the Word to be born, this is because this eternal Word has always been the eternal Son.

This reference of Jesus’ body to the Father explains why his body can be “full of truth.” Our body is the first space of truth because it keeps the memory that we have not given life to ourselves, but that we come from a primordial gift received from the Creator through our parents. Thus, our body is the first space of truth because it is the space where we can remember the original action of God, who created us. Only by manifesting this primordial origin can the body open our life beyond ourselves, so that a correspondence or adequation is possible between us and the world. Thus, truth consists in the capacity of the flesh to unveil the Creator and Father, and thus it consists in the capacity of the flesh to acquire a filial meaning.

Now, what happens in every human body, and what is the central axis of the truth of the body, has happened in Jesus in a supreme and unique way, because He is the eternal Son of God born in the flesh. The body of Jesus not only speaks (as every human body does) of the Creator of the world, but it reveals to us God as the Father who always had a Son and who, in giving up his Son for us, has given himself. Thus, the flesh of Jesus is full of truth because it manifests the Origin of everything and enables us to recognize this Origin and in turn to be born of Him (cf. Jn 1:12-13: “Those who believe in his name … were born of God”).

In short, truth is manifested in the human body, because the body is the space of filiation, and thus Jesus’ body is the fulfillment of bodiliness. It is clear, then, that truth carries within itself love, the love of the Son who receives everything from his Father. This is why we can speak of “the grace [or gift] of truth” (Jn 1:14).

But this filial dimension is not the only one that constitutes the truth of the body.

b) “Worship in Spirit and in Truth” (Jn 4:23)

A second element of truth that manifests itself in the body appears in Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman. St. John presents the scene on a double level: the historical level of the woman Jesus encounters, and the symbolic level in which the woman represents Samaria, separated from Israel. On this second level, Jesus, appears as Israel’s bridegroom, as John the Baptist had pointed out (Jn 3:29), and as he revealed himself in his first public sign at the wedding at Cana (Jn 2:1-11). For this reason, the false love of the Samaritan woman goes hand in hand with the Samaritans’ false worship on Mount Gerizim that constitutes adultery against the true God (cf. L. Alonso Schökel, Símbolos matrimoniales en la Biblia, Estella [Navarra], Verbo Divino, 1997, 179-184).

What does it mean, in this context, to “worship in Spirit and truth”? Jesus says that soon the temple of Jerusalem will give place to a new temple, which the reader already knows is Jesus’ risen body (Jn 2:21). To worship in truth, therefore, is to worship from within the body of Christ, which implies that we worship from within the order of personal relationships he lived out in his own body and taught us to live. It is precisely in this place of the body of Christ (and only in this place) that the Spirit is poured out, and therefore it is possible to worship “in Spirit and truth.”

The body of Christ now appears not only as open to the Father (filial meaning), but also as capable of incorporating the believers into Jesus himself (cf. Jn 1:13). This means that, besides the filial meaning of the body, there is also a spousal meaning, as the context of the dialogue with the Samaritan woman confirms. Christ’s presence is the gift that enables the Samaritan woman to ask for the water of life, so that her faith incorporates her into Jesus and she is able to give true worship to God. On the other hand, to be incorporated into this new body of Christ the bridegroom, it is necessary to accept the truth of the created body, which is the truth of the union of man and woman since the beginning, that is, the truth of the relational order proper to marriage. Thus, Jesus reminds the woman: “you have had five husbands, and the one you have now is not your husband” (Jn 4:18).

Truth is manifested, therefore, in a body that is given up and, when the gift is accepted, generates a unity of vision. As Genesis says: “Adam knew Eve his wife” (Gen 4:1). And the prophet Hosea moved from this spousal knowledge to the knowledge of the God of the covenant. Notice how Jesus follows the same path here by saying to the woman: “If you knew the gift of God…” (Jn 4:10) and by inviting her to stop worshipping “the one whom she does not know” (cf. Jn 4:22), that is, the idol (cf. Dt 11:28: “following other gods that you have not known”).

In conclusion, Christ is the truth because he raised the spousal gift of the body to a whole new level. This is brought to fulfillment in the Eucharist, where his body is radically associated with the gift of self: this is “my flesh for the life of the world” (Jn 6:51). Only by receiving this gift can we attain the full knowledge that life is received from the Creator so that we can become one body among ourselves. Consequently, through this gift truth is connected to human action and thus to freedom.

c) “The Truth Will Make You Free” (Jn 8:32)

Jesus’ sentence that unites truth and freedom takes its background from the Old Testament. Jesus pronounces it in the temple, during the Feast of the Tabernacles, when the courtyard of the sanctuary was full with water containers and, at nightfall, with great torches. This powerful symbol recalled the liberation of Israel from Egypt. While crossing the desert, the people drank water from the rock and were guided by a pillar of fire. In this context Jesus presents himself as the source of living water (Jn 7:37-38) and as the light of the world (Jn 9:5), thus confirming that he is the true temple.

Therefore, when Jesus says: “the truth will make you free,” the truth is again associated with the space of his body-temple, now seen as a place of liberation from slavery. The truth that sets us free starts with the encounter with the incarnate Son, who calls us to follow him and to be incorporated into him. Thus, we can perceive God’s will as a fatherly will, showing us the path towards filial flourishing. In this way Jesus brings the Old Testament law to its fullness. For this law remained ultimately outside of man, while Jesus conforms us interiorly to his filial heart, obedient to the Father’s will. This is why truth is seen in this text as the fulfillment of the law, as was already the case in the Prologue of John’s Gospel: “The law indeed was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ” (Jn 1:17).

The sentence “the truth will make you free” (Jn 8:32) goes in parallel, then, with “the Son makes you free” (Jn 8:36). This means that, in order to exercise freedom, we need to return to our Father’s home. Freedom is possible only by living in harmony with the place one inhabits. For it is thanks to this harmony that every work we do not only improves our surroundings, but improve as well the one who engages in this work who that sees his surroundings as his own home. The opposite happens with the slave, whose work remains outside himself, so that he is divided. Jesus brings full freedom because he brings a new situation in the world, a new dwelling place that we recognize as our Father’s home. This space is in the first place the space of Jesus’ body, into which we can be incorporated, and where we enter into a covenant with God and with our brothers and sisters. The truth sets us free, because it is a freedom that builds us up.

We can conclude that truth consists of the configuration (or architecture) of that space of corporeal relationships where one can act freely, because this space is configured as the Father’s home. That is why the freedom brough about by truth does not consist in the absence of bonds, but in the presence of precisely those bonds that, like the roots of a tree, regenerate our desires and promote our free activity.

This context of liberation highlights the dynamic character of truth, which sets man in motion towards his flourishing. Truth, then, is—and here again we see how the Gospel takes up the Old Testament tradition—the correspondence between what is said and what is done, between the person and his faithful action, sustained day by day. From this vantage point we can also see that truth can be spelled out only throughout the time of a whole life. Therefore, there are also true ways of living time, that is, there are times full of truth. True times are those whose rhythm allows us to perceive the Father’s design for our life, from the memory of his gifts to their fruitfulness.

Thus, truth is not only what there is, but what there can be. It is not only what we are, but what we are called to be. For he who is open to the light that comes from the Creator can inaugurate new worlds, like the artist who, from what he sees, generates and transmits a new vision.

The experience of truth is thus connected to what parents do when they give a name to their child. For, as they acknowledge what the right name is, the one that best suits the child, they understand that it is a name full of new promises. The truth of the name they impose depends on the greatness of horizons that their child will inaugurate in the future. Here we have the generative aspect of truth, which is united to the filial and spousal aspects mentioned above, confirming once again that truth opens up to love.

d) “I Am the Way, the Truth, and the Life” (Jn 14:6)

During the Last Supper, Jesus presents himself as the truth in person, which allows us to weave together the different threads we have described so far. The context is crucial, for the Master speaks of the many dwelling places he prepares for his disciples in his Father’s house (or temple) (Jn 14:1-3). We know that the true temple is the body of Jesus, and that the dwelling places are our incorporation into this body, an incorporation made possible after the resurrection: “There are many dwellings in the house, as there are many members in the body,” St. Irenaeus of Lyons says (Adv. Haer. III 19,3: Sources Chrétiennes 211, 79).

This context of the dwelling places of the temple helps us to interpret Jesus’ words: “I am the way, the truth and the life” (Jn 14:6). The “way” corresponds in this sentence to the building up of the dwelling place or temple. We already noticed that the truth indicates the architecture of this dwelling place.

According to this connection, it is not enough to say that Jesus is the way to truth and life, which would be the final destination of the journey. It seems rather that the way, the truth and the life are part of the journey towards the Father, and that the only final destination is the Father himself. We have already seen, in fact, that the truth is opened to us in the flesh of Jesus, because through his flesh we can attain the knowledge of the Father, as well as the filial freedom necessary to build the house. And life is also the life of Jesus in his body, which will reach its fullness at his resurrection, so that his disciples can participate in it.

All this invites us to interpret “I am the way, the truth and the life” in connection with a verse from Hebrews, which speaks of the “the new and living way that he opened for us through the curtain (that is, through his flesh),” to enter the sanctuary, which is the presence of God (Heb 10:20).

Jesus is a living way (the way and, at the same time, the life) because he is a personal way, that is, a person who opens the way and leads us along it, so that we arrive to the true, heavenly sanctuary. The fact that he is a living way explains how the goal can be anticipated, since it is characteristic of living beings that, although they grow towards fullness, they do so by being alive at each moment of their journey. In this, living beings are different from the products of human hands, for a car is only a car when the last wheel has been put on. Therefore, when Jesus presents himself as the way to the Father, he affirms, at the same time, that whoever has seen him has seen the Father. This is in agreement with the sacramental logic, where the sacrament is a sign that realizes what it signifies.

The Letter to the Hebrews adds that the way is new because Jesus has opened it through the veil, which is his risen body. Once again, we see a connection with the dwelling places of the Father’s house (Jn 14:2), which are new because Jesus inaugurates them in his body, given up and resurrected for us. This in turn highlights the communicative aspect implicit in Jesus being “the truth”: he is the truth insofar as he is the Word made flesh, who awakens us from our isolated sleep and introduces us into the shared space of the world.

“I am the truth” means, then: “behold, a body that manifests the Father and the fullness of his designs; behold, a space into which every person can be incorporated to contemplate this manifestation of the Father and participate in it.” This is why Jesus is not only the fullness of truth, but also someone capable of fully communicating this truth, for he does not leave his disciples orphans (Jn 14:18) but, on the contrary, he prepares a dwelling place for them.

All of this shows us that the truth that is Jesus cannot be separated from love. This becomes even clearer when we continue reading what he says after he identifies himself with the truth. In fact, the space of truth that Jesus opens for us is the space of the encounter between Father and Son: “I am in the Father and the Father is in me” (Jn 14:11). Therefore, the Christian who is incorporated into the body of Jesus is incorporated into a communion between Father and Son, a communion that becomes interior to the Christian himself, who becomes a dwelling place: “we will come to him and make our home in him” (Jn 14:23). This transformation from the dwelling place of Jesus’ body to the interior dwelling place of love happens thanks to the Spirit, whom Jesus calls here “the Spirit of truth” (Jn 14:17). Love is thus inseparable from the order of the body of Christ, an order, as we have seen, that is filial, spousal, and generative.

After presenting himself as “the way, the truth and the life,” Jesus makes another reference to truth in his priestly prayer, where he asks the Father: “sanctify them in the truth” (Jn 17:17). According to de la Potterie, the expression “in the truth” has a spatial sense (‘within’ the truth), and confirms our reading of ‘truth’ as the space of the temple of the body of Jesus where full communion with the Father and with each other can take place (cf. I. de la Potterie, La vérité dans Saint Jean, op. cit., vol. II, 756). It is in this body-temple that Jesus sanctifies himself, bringing this body into full unity with the Father. And it is in this body-temple that he sanctifies us, by communicating to us his own communion with the Father.

This fullness of truth in Jesus helps us better to understand his conversation with Pontius Pilate. Jesus associates his kingship with the witness to truth, for which he was born and came into the world (Jn 18, 37-38). If truth makes Jesus king, it is because his truth is not a private truth, but a truth able to transform the relationships among men. Jesus is king because he opens up the concrete space of personal relationships where full communication with the Father and among human beings is possible. This is the space inhabited by those who “belong to the truth,” so that they can hear the voice of truth.

As Jesus says to Pilate, his kingdom is not from this world. This is because the truth of love (the truth of our relationships) is at war with the truth of this world, a truth conceived as mere dominion or power. However, even Pilate, who has power in this world, receives such power from the source of truth, which is God the Creator and Father. The truth that Jesus brings, therefore, aims at illuminating human life in society in this world. In fact, Christian truth, as the truth of love—a truth on which the dignity of each person rests—presents itself before the world as the definitive judgment on the world. St. John sees a sign of this judgment when Pilate, at high noon, the hour of greatest light, without suspecting the mystery hidden in his mockery, makes Jesus sit in the judge’s seat (Jn 19:13).

4. Conclusion: Eucharistic Truth

We can conclude that truth is fully revealed in the space of relationships opened by the body of Christ. This is a body full of truth because it manifests a filial relationship to the Father. Moreover, this is a body that opens itself up to the body of the Church-Bride, so that she can adore in Spirit and truth. In this way, the truth that shines in the body frees up the human being, transforming him, so that he can tend towards his own fullness in relationship to God. Jesus brings about this truth in his Passion, Cross and Resurrection, and recapitulates it in his rite at the Last Supper.

The Eucharistic rite allows us to conclude what the truth of Jesus is all about. The confession: “Jesus is the truth” must be read from the viewpoint of the Eucharist. For it is in the Eucharist that we are introduced into the space from which to contemplate the truth: the space of Jesus’ body is built up by the Father (“he took the bread and gave thanks”) and is able to embrace his brothers and sisters in order to generate life in them (it is “given for you,” “for the life of the world”). Therefore, in his priestly prayer Jesus asks the Father to glorify his Son, as the Father has given him “authority over all flesh” so as “to give eternal life” to as many as the Father has given him (Jn 17:2). What Jesus is asking of the Father is to incorporate these into his risen body, which is the Eucharistic body. He then defines this risen life in the flesh as access to the truth: “This is eternal life, that they may know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.” (Jn 17:3).

The relationship between truth and love is thus made clear, a relationship that allows us to describe Jesus’ truth as the truth of love, and to speak of “loving in truth” (2 Jn 1; 3 Jn 1). For this is not a truth that is contemplated from afar, but a truth that calls us to participate in it, in a similar way as Jesus invites us to take and eat of his body. Moreover, the truth revealed in Jesus’ body manifests Jesus’ gratitude to the Father as well as Jesus’ self-giving for us. Therefore, this truth revealed in the body corresponds to the knowledge of love, the love of the Father and the Son together with brotherly love. Let us recall that it is at the Last Supper where John presents his doctrine on love: Jesus loves us to the end (Jn 13:1) and commands us to love one another as he loved us (Jn 13:34-35), that is, as the Father loved him (Jn 15:9).

According to St. Ignatius of Antioch, “faith is the flesh, charity is the blood” (Epistle to the Trallians 8). In associating faith and flesh, the martyr confirms what we are saying. For faith is the response proper to one who recognizes the truth. Therefore, faith is linked to the flesh of the Word, where this truth is made known to us. Ignatius himself uses the adverb “truly” to refer to the mysteries in the flesh of Jesus, which were not mere appearance, as the Gnostic thought. And what about the blood, according to Ignatius? It is associated with love, because it is the blood of the covenant that Jesus pours out for us, thus evoking the Spirit of life and communion. The Eucharistic union of flesh and blood runs parallel, therefore, to the union of truth and love.

One can find here the reason why Jesus preached “as one having authority, and not as the scribes” (cf. Mk 1:22). His authority comes from the correspondence or adequation between his word and his body, between what he says and his way of living all his relationships. This adequation means that what Jesus teaches coincides with the original language that the Father Creator has written in our bodies, a language that allows us to confess him as the source of all we are and all we do. That is why Jesus affirms that his doctrine is not his own (Jn 7:16). Thanks to this reference to the Father, Jesus’ word is full of authority because it is a word that confers a new form upon our relationships. The word of full authority, from which the authority of the rest of his words springs, is the one he pronounces over his body and blood: “Giving thanks, he said: Take, eat; take, drink…” Nil hoc verbo veritatis verius: there is nothing truer than this word of truth.

“Just as Jesus Christ went unrecognized among men, so does his truth appear without external difference among common modes of thought. So too does the Eucharist remain among common bread.” These are the words of Pascal (Pensées, 789, ed. L. Brunschvicg; quoted in John Paul II, Encyclical Fides et Ratio, n. 13). Recognizing the truth among different opinions is equivalent here to recognizing a body among other bodies. It is a matter of recognizing, among other bodies, the personal body that opens for us an encounter that generates a common vision. It is a matter of recognizing, among other bodies, the body of Jesus, where the language of each personal body reaches its fullness, for Jesus’ body opens us to the full knowledge of the Father and of our brothers and sisters.

This vision of Jesus as the truth of love offers us a key to entering into the mystery of Christ. The early Church developed an ontological Christology, which looked at the being of Jesus as Son of God and Son of man. The last century focused on articulating a Christology of Jesus’ consciousness and of his freedom. The latter was a question proper to the context of Modernity, which, although rich in many respects, showed its limits by focusing excessively on the idea of an autonomous subject. While acknowledging that these approaches are necessary, in this paper I have highlighted the new relationships that Jesus opens in his body, with the Father, with our fellow brethren and with the world. This proposal leads to a Eucharistic Christology, which presents Jesus as the full unity of truth and love.

Through the unity of truth and love in Jesus, we have access to his complete mystery. First, such unity between truth and love as we see happening in Jesus is only possible if Christ is the Son of God. In fact, we can proclaim all that is true as lovable and all that is lovable as true only through the filial acceptance of a Creator who is also a Father, an acceptance Jesus lived out in fullness. Second, the unity of truth and love in Christ proves that he has assumed all that is human (including affections, intelligence and will) for only in this way can he redeem our capacity for true love. Finally, by his way of uniting truth and love, Christ has shown the way in which he unites in himself God and man, with an unsurpassable unity that, at the same time, keeps the proper distinction between the original source and the one who receives love and thus is able, in turn, to give himself to others. In short, the truth of love offers a key to entering into the entire mystery of Jesus. Christ has not only healed the rupture of truth and love that constitutes man’s sin, but he has elevated to an unsurpassable degree the original unity of truth and love as it had been given in creation.

This view of Christ has consequences for the contemporary debate on truth, also within the Church:

- For instance, who considers Christian doctrine a beautiful ideal unaffected by changes in pastoral practice separates the truth of Jesus from the love of Jesus, which can only be done by separating the Logos (truth) from his flesh (love and pastoral care). Therefore, the separation between truth and love, doctrine and mercy, theory and practice, creates a fracture within Christ himself. Christ the Shepherd is thus separated from Christ the Teacher, or the devotional Christ of prayer from the Christ who reveals himself in the liturgy and in the public life of the Church. We ask, then, with St. Paul: “Has Christ been divided?” (1Cor 1:13). On the contrary, in him we do not only find fulfilled unity, but even a source of unity for all that is broken in our world.

- Whoever denies that there is a language of the body, a language that assures the unity of love and truth, creates a separation between Christ and the rest of us. For without a language of the body, shared by all humanity, it is impossible to explain how Christ, by assuming the flesh, assumed in himself all human beings and communicated his life to them. And it is also impossible to explain how the sacraments transform, not only our capacity to judge and to act, but our very being, for they bestow upon us a new identity.

- Those who see the Christian way of life as a beautiful but unattainable ideal do so by weakening the reality of the Incarnation and of its sacramental communication to us. They consider the unity of truth and love something to be achieved only at the end of time. Without acknowledging that this unity has already taken place in the risen Christ. According to them, Christ has brought us only a truth without flesh, which, in turn, leaves us with living in the flesh without truth. But such conclusion amounts to a denial of the Christian way of life as the only possible way of human flourishing.

I would like to conclude by quoting St. Augustine, a great witness to this unity of truth and love. The Bishop of Hippo frequently refers in his works to the biblical unity between mercy (love) and truth, where he discovers a recapitulation, as it were, of God’s plans. Psalm 25 says, for example, that “all the ways of the Lord are mercy and truth” (Ps 25:10; cf. Tob 3:12) and the same connection is found in many other psalms (cf. Ps 57:10; Ps 89:14; Ps 100:5; Ps 108:4; Ps 117:2).

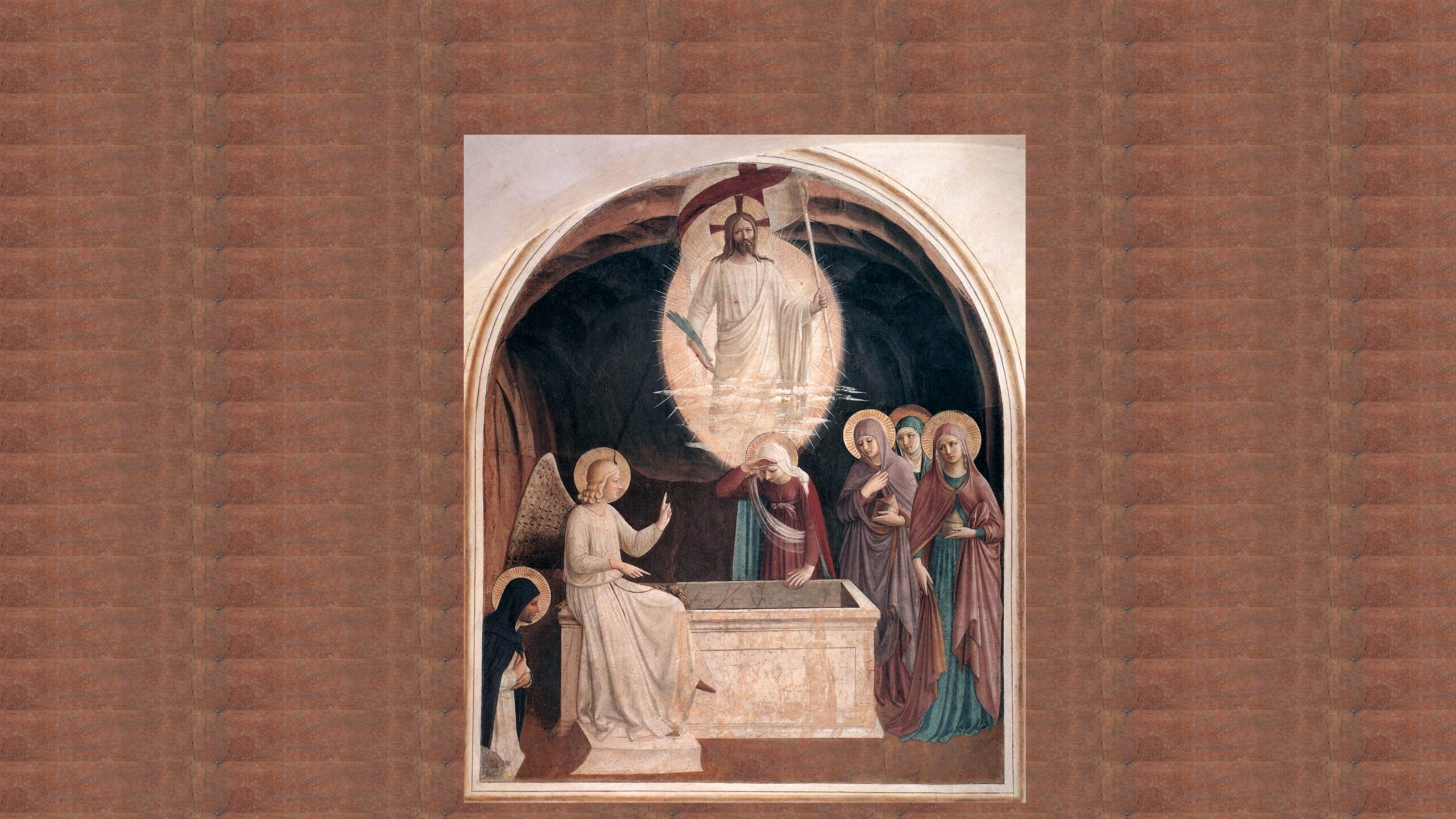

Now, Augustine sees this harmony personified in Jesus: “We see that Christ himself is mercy and truth” (Enarr in Psalm. 56,10 [CCSL 39, line 16]). This happens, first of all, in the Incarnation, to which Augustine applies the verse: “truth is born of the earth” by interpreting it as: “the Word is born of Mary” (Enarr. in Psalm. 84,13 [CCSL 39, line 2]). For the truth, being born of the flesh, can die for us, thus revealing his mercy. The resurrection underscores again the passage from mercy to truth, for it consists in the full justification of man, where Jesus shows himself fully true and trustworthy in his promises (Enarr. in Psalm. 56, 10 [CCSL 39, lines 16-22]). Augustine applies the distinction between mercy and truth to Jesus’ first and second coming as well, for in the first he came to have mercy, in the second he will bring the full revelation of justice and truth (Enarr. in Psalm. 24, 10 [CCSL 38, line 1]).

Thus, St. Augustine sees in the confession of the unity of truth and love the confession of the unity of the entire work of Jesus, who takes on flesh to die and rise in the flesh and to allow us to be truly incorporated into him. This correspondence between truth and love, thanks to which the life of Jesus is a path for man towards fulfillment, makes it possible for Bernard of Clairvaux to say: “not only truth, but also love will set us free” (Epistle 233, par. 3, Opera omnia, vol. 8, p. 106).

Share this article

About Us

The Veritas Amoris Project focuses on the truth of love as a key to understanding the mystery of God, the human person and the world, convinced that this perspective provides an integral and fruitful pastoral approach.