What Joy of Living? A “Wonderful Feeling” or the Fullness of Action?

Laetitia Calmeyn

“A wonderful feeling” is the expression found in number 1 of the basic text of the Pontifical Academy for Life, entitled “A Theological Ethics of Life”[1] published in 2022. The document includes several examples of experiences of joy to introduce an ethic of life. But what joy and what life are we talking about? While it is obviously legitimate to experience joy also through feelings, Christian joy cannot be reduced to a feeling. How can joy be a criterion for developing an ethic of life?

We will first take up the notions of “life” and “joy” from a theological and biblical perspective so as to extract from them some criteria for discernment also to relate to certain questions addressed in the document of the Pontifical Academy for Life.

It seemed to me that the way the notions of “joy” and “life” were presented in the proceedings of the Colloquium also reflects a research method that deserves to be questioned. The transdisciplinary approach that was adopted involves different sciences, including theology. How is one to understand this term “transdisciplinarity”? Does it correspond to the fullness of the theological act which allows the sciences to order themselves to the service of a greater knowledge of the mystery of God and the mystery of man? Compared to what is usually called “interdisciplinarity,” transdisciplinarity seems to be devoid of theological purpose, at the risk of imprisoning, through lack of articulation, all knowledge in an incoherent and illusory “autonomy.”

1. “Communion, Life, and Joy” in Scripture and Tradition

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us, joy is a fruit of the Holy Spirit[2]. This means that the person who benefits from this fruit associates himself with the union of Jesus with his Father. This union is in the Holy Spirit, the source of Life for that person. The vocation of every baptized person is to live this Eternal Life so that it unfolds across the various dimensions of his humanity, in thought, word, and deed. Let us remember that the first fruit of the Spirit is charity. This theological virtue disposes us to participate in the very love of God, in his Being, that is to say in the unity of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. This participation in the divine unity is experienced through acts that fully engage us and which open up access to a fullness. There is at the heart of the human act this passage from domination to service. If the act commits me humanly, this commitment is fully realized only in covenant, only in response to God who shows me the paths of truth and life, who allows me to participate in his very goodness. From mastery in action, I pass to the service of divine action. The attitude of a servant is one that allows me to receive this fullness of Life that springs from the heart of the action, to discern the divine goodness in order to conform to it. Human action then becomes a source of joy. Joy corresponds in a way to how we adjust ourselves to the love of delight that is of and in God. The Father delights in the Son and from their unity proceeds the Holy Spirit in whom the Father and the Son delight. Baptism associates us with this love of delight through each created reality and allows us to consent to the gift that we are for ourselves in order to live from this gift. Donation is the soul of all human action. Given to himself, the human being is called to receive himself in order to give himself. While this relationship to the gift has been damaged by sin, redemption reveals its full meaning to us. More than giving myself, by the grace of baptism, I am called to give the Life of Christ.

In order to address the fullness of action, we will look at the meaning of Christian marriage. It expresses our participation in Trinitarian love. The child, the fruit of the union, originates in this Trinitarian communion in which the spouses participate by the grace of Christ. The conjugal union carries within it the unity of union and procreation, which from Genesis is presented as a law of nature. Its possible dissociation mentioned in the proceedings of the colloquium of the Pontifical Academy for Life (e.g. contraception, homologous insemination) seems to me difficult to sustain. With the help of some biblical and theological foundations, we will try to understand why.

While sin has caused a rift in the relationship of Creator and creature, the Lord renews his Covenant through the gift of the Law. We will see how the inner logic of the Decalogue leads us to rediscover the meaning of this law of creation inscribed by God in our hearts, the Incarnation giving us its full meaning.

Let us go back to what Genesis says.

a. Genesis 1-2

The book of Genesis presents the creation of the human being in terms of image. “Let us make man in our image.” There is a plural that presides over the act that creates the human being. The originality of the creation of the human being lies in the fact that he is created from within the divine communion, and the vocation of resemblance consists in participating in this life of communion. But to do this requires, as in God, a radical otherness. Otherness is the very mark of the Creator in our being. The human being participates in the divine communion through this radical otherness that is willed by God: the being male and female the being. The poetry of the text clearly reveals this: “God created man in his own image. In the image of God he created him.” In the continuation of the verse the word “image” disappears and receives its explanation in the expression “male and female he created them.”

After the man and the woman were created, the Lord blesses them, saying to them “Be fruitful.” Unlike with the animals, who receive the blessing and to whom God says, “Be fruitful,” the word addressed to man is a responsibility. This appears clearly through the expression “He told them.” God entrusts his word of life to man and woman by calling upon the human being to give life. According to the Hebrew, it is a “fructification,” a making fruitful of all the dimensions of the human person, calling for the commitment of all these dimensions. This relationship to the gift of life, to the fact of their receiving life together as a gift, is what makes communion possible. This communion will then extend to all of creation. Dominion consists in making the gift of life grow through expression in each of the creatures.

The second account of creation in the Book of Genesis reminds us that this gift of life is first and foremost spiritual. “God formed man of dust from the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life.” And it is because he is spiritual that he will unfold psychically and bodily. This biblical element is decisive for an ethic of life. In theology, the ethic of life derives only from eternal life, from the Word of Life, as Saint John will make explicit. It is this relationship to eternal life that allows man to fulfill his vocation to communion through all the dimensions of his humanity (body, soul, and spirit).

b. The Decalogue

Tradition presents the Ten Commandments to us as the path proposed to man to rediscover the meaning of his vocation to be an image, to a communion that is a source of life. Without repeating all the commandments here, it nevertheless seems interesting to me to dwell on the internal logic which unites the third and fourth commandments, one concerning the Sabbath, the other the relationship to parents. The Sabbath corresponds to the rest of God in his creation. It is by resting, by settling down again, by continuing to give it life that God completes all creation. Keeping holy the Sabbath means acknowledging this gift of life and celebrating it in our lives. The Eucharist commemorates the fulfillment of God’s rest in his creation through the death and resurrection of Christ. We are in communion with the gift that Christ makes of his life. This gift is now for us the source of all human life and of all communion. It is also the summit.

By flowing from the sacrament of the Eucharist, the sacrament of marriage expresses the Eucharist’s meaning. As Saint Paul reminds us in the Epistle to the Ephesians, it is a question of loving one’s spouse as Christ loves the Church, laying down his life for her. It is from this mutual gift that life springs for each of them and especially for the child. This relationship to life opens the conjugal act to its full significance.

The fourth commandment calls us to honor father and mother, with the precept specifying: “in order to have a long life.” In Hebrew, it is a matter of “glorifying” one’s father and mother. This verb is usually used to qualify our relationship with God, a relationship of thanksgiving. “Honoring one’s father and mother” means fulfilling one’s vocation to be in the image of God: receiving through our parents the life of God in order to give it in a relationship of communion. It is this relationship to life as gift from God given to each person that then makes it possible not to kill, not to commit adultery, etc.

c. A Résumé of the Gospel

In a meditation on the “disinterested gift”[3] written in 1994, John Paul II reminds us that the joy of communion can only be experienced by recognizing how the other is given to himself, by contemplating the way in which the Lord delights in the creature through this gift of life given to each person. In the order of creation, the human being is gift, in the order of redemption he is forgiveness. This means that he no longer receives himself only from creative love, but more deeply from redemptive love. The gift of creation is enriched by the offering of the Son of God who gave his life for each of us. Whether or not they are aware of it, all human beings are now marked by the gift that Christ makes to us of his life. This divine life comes as enfolding every human being. Baptism consists in responding to this gift in order to live it, thus participating in Christ’s divine communion through every relationship. This participation engages our whole person and enables us to participate in the joy of Christ which becomes our joy.

Does not the first epistle of Saint John remind us of this: “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life—the life was made manifest, and we saw it, and testify to it, and proclaim to you the eternal life which was with the Father and was made manifest to us—that which we have seen and heard we proclaim also to you, so that you may have fellowship with us; and our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ. And we are writing this that our joy may be complete” (1 Jn 1:1-4).

Joy implies living in communion, a communion that becomes good news for everyone and to which, through the Incarnation, we have access through all the dimensions of our humanity: body, soul, and spirit. This communion, which implies the total commitment of our person, is a path of unification of the person and of unity of the human race.

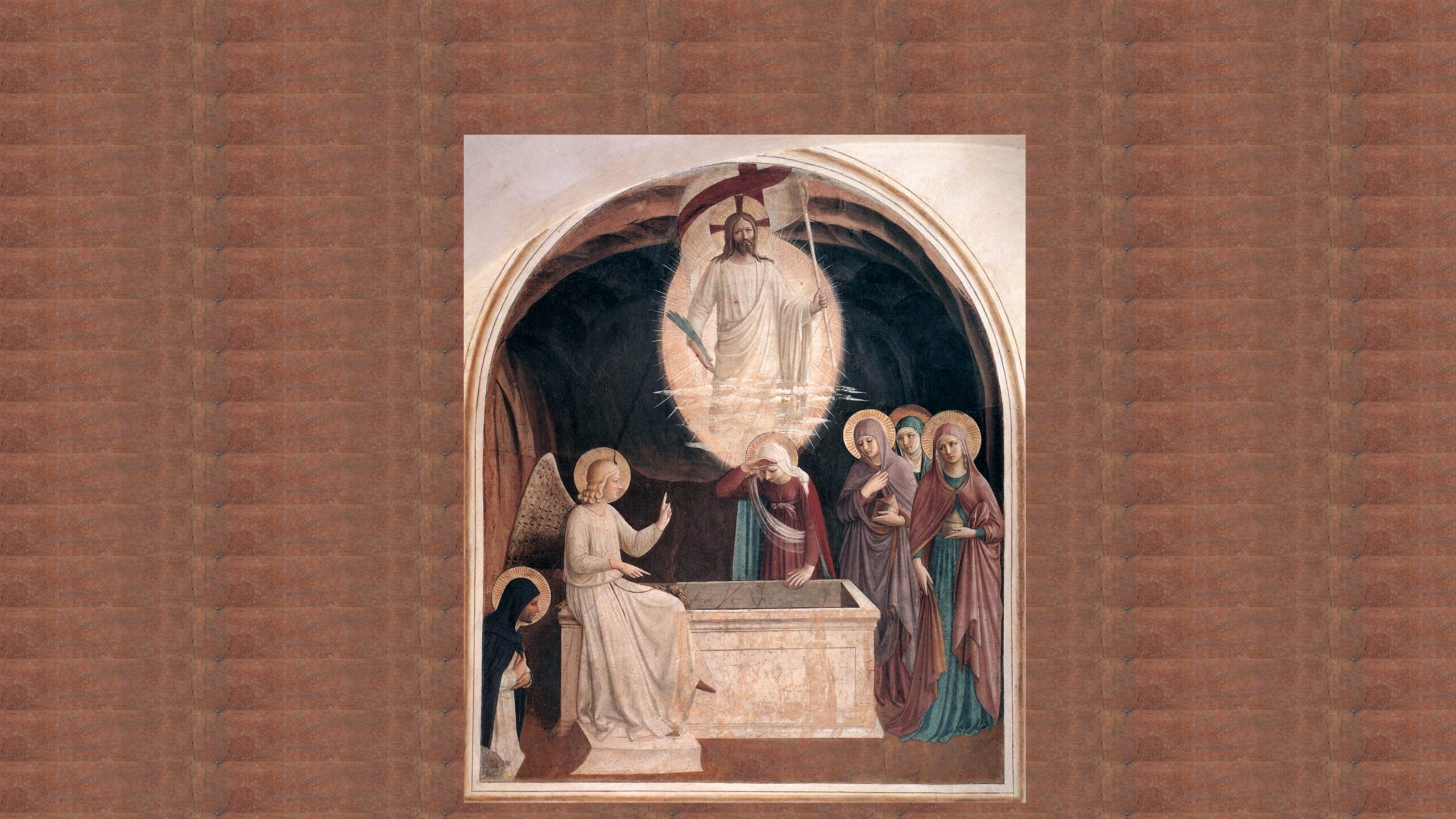

John the Evangelist not only takes us back to the beginning of creation, but more profoundly, he reveals to us that the divine beginning is that of the Word of Life. In chapter 16 of the Fourth Gospel, Jesus, at the moment of entering into his Passion, speaks to his disciples of this joy of communion by referring to the image of a woman giving birth: “Truly, truly I say, you will weep and wail and the world will rejoice; you will be sad, but your sadness will turn into joy. A woman about to give birth is saddened because her time has come; but when she gives birth to the child, she will no longer remember the pains in the joy that a man has come into the world” (Jn 16: 20-21). The pains of childbirth appear in the Book of Genesis as a consequence of sin which particularly affects women: “I will multiply the pains of your pregnancies, the pains of childbirth.” The term “multiplication” corresponds to that of fructification. It is linked to the gift of life. God continues to give life, but the sin that has distanced us from God makes this gift more difficult to accept, hence the pain. When Jesus gives himself to his disciples at the Last Supper, he expresses the overabundance of God’s gift to man to such an extent that he takes upon himself our inability to receive this gift, and it is in this way that he gives himself even more, that he gives us the opportunity to discover that life is deeper than death, suffering, and evil. This is the profound reason for our joy given in every Eucharist.

Let us note that whenever the Gospel of John speaks of the joy of the world, the subject of this joy is the world, whereas the joy of the disciples comes from beyond themselves. It is a gift. In the Bible, joy is a gift that God gives to the humble and to those who are faithful. It is more profound than the ordeal of injustice, persecution, and suffering, and it expresses the intimate relationship of Jesus to his Father given to the little ones as a gift (Lk 10:21ff). It is the expression of communion as it is the source of eternal life.

Joy as a gift expresses the fullness of an action. It is not so much about the fullness of our own action but about the way in which the Holy Spirit completes every good action, since it is a participation in the goodness of God. In the Son, the good deed is an offering to the Father, confirmed by the gift of the Holy Spirit who makes it fruitful. So it is for us, the fullness of action is the fact that the human act is a participation in the eternal thanksgiving of Our Lord, source of communion and life.

2. Which Theological Method?

The Proceedings of the Pontifical Academy for Life pose several questions also in the methodological order:

In order to reconcile theology with pastoral care, the document appeals to an “ethics of life.” But is not this Life the heart of every theological approach, since the object that is God is also its subject? Is he not the one who communicates to us the Word of Life? The Word of God is the source of Life. When we read the Holy Scripture, the Word contained in the text, to which we have access first of all through the literal meaning, enlightens our life. Let us take up the definition that Saint Thomas gives of the literal meaning in the Quodlibet, as well as in question 1 of the Prima Pars of the Summa Theologica: “The literal meaning is the reality signified by the letter.” Although exegetical methods clarify the text for us, helping us to reach its literal meaning, it is still necessary to have a reading that is carried by the faith of the Church. It is in the light of faith that reason discerns the reality signified by the letter. This reality is found in every hour of history enriched by the gift of the Holy Spirit who gives us its meaning for our lives. This meaning is that of faith, also called allegory. The reality signified by the letter never ceases to open my intelligence to the given of faith, which is the event of the incarnation, of the redemption, of the Trinitarian revelation. This deeper understanding of dogma based on Scripture increasingly leads to an anthropology and a morality of communion that is the source of eternal life (eschatological or anagogical meaning). As rooted in the Word of God, moral theology cannot in this sense suffer from a contradiction between faith and morality, between thought and life, between morality and pastoral care. The approach of the Pontifical Academy for Life denounces these contradictions and tries to overcome them through a transdisciplinarity that ends up denying the properly dialogical vocation of theology. As Scripture and Tradition attest, theology is inherently interdisciplinary. The Word of God never ceases to shed light on scientific research, from which it also receives new ways of deepening the mystery of God and the mystery of man. Professor Jérôme Lejeune was thus able to testify to the way in which faith illuminates and directs the scientific approach and how the scientific approach can account for what is given by faith, for example on the question of the beginnings.

Transdisciplinarity seems to situate research in an autonomy that denies the roots and consistency specific to each discipline, in particular theology. Under the pretext of an illusory relationship to life, it can justify new norms that supposedly reconcile theory and praxis, morality and pastoral care, faith and life, etc.

At base, this approach merely reproduces the sin of our first parents. “If you eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you will be like gods.” To pose as masters of what is good and what is evil leads us to the pretense of being “like the gods,” that is, to an idolatry that forgets the constitutive unity of our humanity.

There can be no ethics of life except in the covenant with God, only in the divine communion to which we accede by baptism, which is the source of eternal life. The traditional doctrine of the four senses of Scripture allows us to understand that there is no separation in theology between theory and praxis, between faith and morals.

To conclude

Our participation in the Trinitarian communion is the act that gives meaning to all our acts. Moral propositions concerning the gift of life cannot in this sense contradict the human vocation to communion. The suffering linked to fertility should lead us rather to propose a pastoral care of communion that takes into account all dimensions of the human person, the life of the couple and the couple’s integration into the community. Fidelity to the law of nature, the revealed law and to the new law, leads us to accompany people in the light of charity that opens us to an ever-new way of linking faith and reason, faith and science.

From this point of view, I understand the importance of interdisciplinarity. The term “transdisciplinarity” raises more questions for me. It seems to introduce more confusion. If we can let ourselves be enlightened by other disciplines, it will always be from the discipline that is specific to us and from which we express ourselves. The term “trans” seems to make disappear the consistency of each discipline and, therefore, also the proper mission of theology which in the Spirit in the light of the Word opens reason and the sciences to their true dimension: the gift of Life.

Trans. John M. Grondelski

[1] V. Paglia, Etica teologica della vita. Scrittura,tradizione,sfidepratiche, Liberia Editrice Vaticana, 2022.

[2] CEC 1832.

[3] John Paul II (2014): “A Meditation on Givenness,” Communio 41, 871-883.

Share this article

About Us

The Veritas Amoris Project focuses on the truth of love as a key to understanding the mystery of God, the human person and the world, convinced that this perspective provides an integral and fruitful pastoral approach.